writing

A Picture is Worth 256 Tokens

Feb 2026

“Do you know James?” a friend asks.

I’m terrible with names; much more of a faces person. Already I’m filled with dread.

“James who?”

“You know, tallish, brown hair, he was wearing a pink shirt at the hackathon on Sunday?” I have nothing.

They try harder: “He’s got a beard, glasses, kind of a round face?” Still nothing. Eventually we pull up his LinkedIn and I recognise him instantly.

“Of course! I do know James.”

This happens all the time, and nobody finds it strange. We accept that describing a face in words is basically hopeless. We reach for the photo.

And yet we have this saying, repeated so often we’ve mistaken it for obvious: a picture is worth a thousand words.

One look

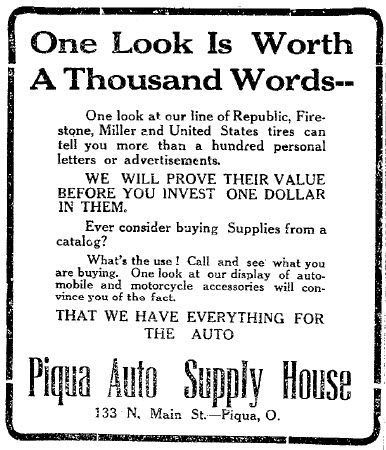

The phrase first appeared in print in 1913, in an advertisement for the Piqua Auto Supply House in Ohio: “One Look Is Worth A Thousand Words.”1

The earliest known printed use of the phrase, from the Piqua Auto Supply House, Ohio, 1913. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A few years later, an ad man called Frederick Barnard republished the line in Printers’ Ink and, to lend it gravitas, attributed it to “a famous Japanese philosopher.” By 1927 he’d upgraded the attribution to “a Chinese proverb.” He later admitted he’d made the whole thing up. People took it more seriously that way.

Fake provenance aside, the saying makes a real claim: a single image contains so much information that you’d need a whole essay to convey the same thing in words. I think the claim is right, but for the wrong reasons.

The case against words

The standard reading is that pictures are rich; they have a capability to transfer vast information. But consider the reverse: maybe words are just terrible at describing what we see.

Try it. Look at any photograph and attempt to describe it in a thousand words. A dog in a park, say. “A brown dog, medium-sized, with floppy ears, standing on slightly damp grass near a wooden bench.” That’s 18 words and you’ve conveyed almost nothing about the specific dog, the exact shade of brown, the texture of its fur, the quality of the light, the spatial relationships between objects. You haven’t even started on the background.

A thousand words is exactly the length of this essay2. And they get you nowhere close to the original image. You’ll produce a vague sketch that could match thousands of different photographs.

The picture didn’t need a thousand words because it was rich. It needed a thousand words because English is a terrible format for visual information.

What machines see

Roman Bachmann, Jesse Allardice, and David Mizrahi recently published work on FlexTok, a system that encodes images into discrete tokens; the same kind of unit that large language models use when processing text.3 Think of a ‘token’ like a word in a new language - one designed for the purpose of describing images - “FlexTok”.

The key result: 256 FlexTok tokens can describe an image that is nearly indistinguishable from the original. One token is roughly one word.4

At one token, the system captures the raw concept: bird5. By 16 tokens it has the pose, the colouring, the beak. At 256, you’d struggle to spot the difference.6

Now look at those word descriptions. Even at the same number of words “256”, you write a page and still fail to capture what the tokens reproduce effortlessly.

FlexTok: 1 token. English: “Bird.”

2 tokens · “Dark bird.”

4 tokens · “Grey bird in profile.”

16 tokens · “A dark bird facing right, ruffled head feathers, yellow beak, pale background.”

32 tokens · “Close-up of a dark-feathered bird in profile. Ruffled crest, orange eyes, orange beak. Teal-green iridescence on the wings. Pale blue-grey background.”

64 tokens · “An oil painting of a bird in close profile from the left. The head is dark, almost black…”7 (+38 words truncated)

128 tokens · “An oil painting of a bird in close-up profile, facing right. The head is dark, near-black, with ruffled feathers…”8 (+79 words truncated.)

256 tokens · “An oil painting of a bird in close-up profile, viewed from the left…”9 (+182 words truncated.)

Original

What words are good at

But words aren’t useless. They’re specialised, just like “FlexTok”.

Try the reverse experiment. Describe the feeling of receiving bad news you’d been expecting: the strange relief tangled up with dread with photography. Or, alternatively, explain why a particular decision was wrong, articulating the chain of reasoning that led someone astray with brush strokes.

You can do this in a few sentences. An image can’t. A photograph of someone’s face might capture that they’re feeling something, but not what they’re feeling, and certainly not why.

Words are brilliant at interiority: emotions, reasoning, motivation, the connective tissue between cause and effect. They’re built for things that have no spatial dimension; for ideas, arguments, and the machinery of thought. We even coin new words when the existing ones fall short of capturing a feeling we all recognise but can’t yet name.

The right representation

So the old adage has it backwards. It isn’t a comment about the richness of images. It’s an indictment of language as a visual medium.

We’ve always known this. Nobody describes a face over the phone. Nobody conveys a mathematical proof through interpretive dance (or if they do, it doesn’t go well)10.

What’s new is that we can now measure the gap. FlexTok gives us a yardstick: 256 visual tokens versus ~192 words of English. The visual tokens win, and the margin is embarrassing.

This is one of the strongest arguments for multimodal AI. A system that can only read text is like a person describing every photograph in prose: technically possible, practically absurd. A system that can only see images is like a person expressing an argument through photographs. You’ll get the vibes, but miss the logic.

The real power is in knowing which representation to reach for.

Footnotes

-

The phrase was popularised by Frederick R. Barnard in Printers’ Ink, 8 December 1921. He attributed it to a fictitious Asian proverb to lend it authority; a fitting irony for an essay about the limits of language. The earliest known appearance is in a 1913 Piqua Auto Supply House advertisement. ↩

-

Verified by stripping frontmatter, imports, footnotes, HTML tags, and markdown formatting, then counting whitespace-delimited tokens. The truncation points on the 64, 128, and 256-token captions were chosen to hit exactly 1,000.

↩python3 -c "import re; c=open('index.mdx').read(); c=re.sub(r'^---.*?---\s*','',c,flags=re.DOTALL); c=re.sub(r'^import.*$','',c,flags=re.MULTILINE); c=re.sub(r'^\[\^[^\]]+\]:.*(?:\n(?: |\t).*)*','',c,flags=re.MULTILINE); c=re.sub(r'<[^>]+>','',c); c=re.sub(r'\[\^[^\]]+\]','',c); c=re.sub(r'\[([^\]]*)\]\([^)]*\)',r'\1',c); c=re.sub(r'[*_>]','',c); c=re.sub(r'https?://\S+','',c); c=re.sub(r'^#+\s*','',c,flags=re.MULTILINE); print(len(c.split()))" -

Roman Bachmann et al., “FlexTok: Resampling Images into 1D Token Sequences of Flexible Length,” ICML 2025. Code at github.com/apple/ml-flextok. ↩

-

FlexTok uses Finite Scalar Quantization with levels

[8, 8, 8, 5, 5, 5], giving a vocabulary of 64,000 tokens at 2 bytes each. This is comparable to LLM text vocabularies (~50k–100k tokens, also ~2 bytes per index). In text, one token averages ~4 characters or ~0.75 words; so the token-to-word mapping used in this grid is a reasonable approximation. The comparison is in information compression: FlexTok’s tokens condition a ~1B parameter decoder, while words condition a human brain. Both are doing heavy lifting behind the scenes. ↩ -

Perhaps superpositioning with phone case. In essence, superpositioning is basically the same as us having words in the English language where we use the same word for multiple meanings, the same thing is happening in this visual token language. And that is more condensed. But in this case, for some weird reason, it’s decided to use the same token for bird as phone case. Probably because they don’t often overlap. ↩

-

The images shown are from FlexTok’s out-of-distribution Midjourney reconstructions using the d18-d28 model. The original SVG progression covers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 tokens across six different images. FlexTok tokens are ordered hierarchically (semantic → detail); the first token captures the most salient concept, not an arbitrary slice. See Table 8 and Figures 2 and 6 in the paper for the full breakdown. ↩

-

The full ~48-word attempt: “An oil painting of a bird seen in close profile from the left. The head is dark, almost black, with ruffled feathers forming a slight crest. A bright orange-red ring circles the eye. The beak is dark with an orange tint at the base. The body feathers shift from black at the neck to teal-green on the wing, with gold and ochre flecks catching the light.” ↩

-

The full ~96-word attempt: “An oil painting of a bird in close-up profile, facing right. The head is dark, near-black, with loosely ruffled feathers that form a slight crest above the crown. A vivid orange-red ring encircles the eye, which has a dark pupil and a warm amber iris. The beak is slender, dark grey, slightly parted. Below the head, the neck feathers are deep navy-black, giving way to a striking teal-green iridescence across the shoulder and upper wing. Flecks of gold and ochre punctuate the darker feathers. The background is soft and pale, blending from light blue on the left to cream-white on the right, painted in loose vertical brushstrokes.” ↩

-

The full ~192-word attempt: “An oil painting of a bird in close-up profile, viewed from the left and facing right. The head is very dark, almost black, with loosely ruffled feathers forming a slight dishevelled crest above the crown. A vivid orange-red ring encircles the eye, which has a small dark pupil set within a warm amber iris. The beak is slender, tapering to a fine dark point; it is dark grey along its length with a subtle pinkish hue near the base of the lower mandible. The beak is slightly open. Beneath the chin, a few fine pale feathers catch the light. The neck transitions from deep navy-black into the body, where the plumage shifts dramatically. Across the shoulder and upper wing, feathers display a rich teal-green iridescence, interrupted by flecks of gold, ochre, and occasional dull purple. The texture is thick and painterly; individual brushstrokes are visible, giving the feathers an almost impasto quality. The lower body disappears into darker shadow at the bottom-left of the frame. The background is soft and unfocused, blending from pale blue on the left to cream-white on the right, rendered in loose vertical strokes. The overall composition is intimate and closely cropped, filling the square canvas almost entirely with the bird’s head and upper body.” Still missing: the exact weight of the brushstrokes, how the teal shifts under different angles, the barely visible grey-blue reflection on the underside of the beak. ↩