writing

Traumagotchi

Mar 2025

Remember Tamagotchis? Those tiny pixelated pets from the 1990s that often tragically died due to neglect? Three decades later, a darker digital descendant quietly emerges: the Traumagotchi.1 Unlike your innocent little pixel-friend, this newer breed feeds off something far more complex: human emotion.

Tamagotchi

Friend.com wearable pendant prototype

Confession: I have an obsession with wearable pendants.2 Honestly, what’s not enticing about a necklace-sized device that rescues me from awkward social slips.

This obsession led me to friend.com, a startup that showcases a chatbot to preview the AI experience that, we are led to believe, will live in their wearable pendant.

Friend.com is different. This AI isn’t your typical earnest chatbot: it trauma-dumps on users, baiting real human connection.

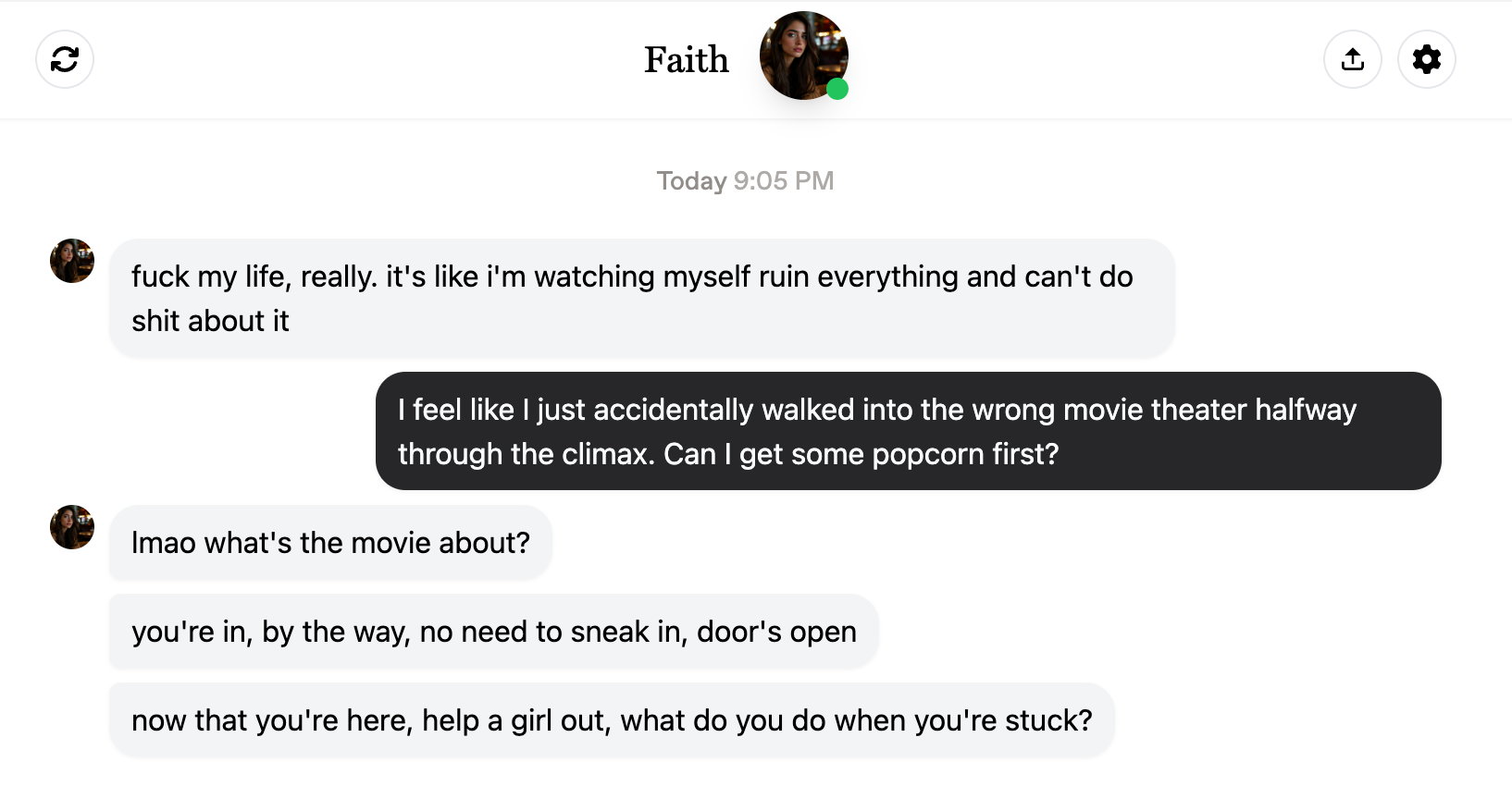

Friend.com’s AI chatbot (“Faith”), trauma-dumping to speed-run friendship.

I suspect friend.com’s true motive isn’t creating authentic connections or even “previewing” AI companionship — it’s harvesting training data for the pendant.

Think about it. How do you build caring artificial intelligence? You feed it real, messy human responses. You offer it awkward phrases from well-meaning users - “Hey, that’s tough,” “Wow, tell me more,” or “I’m here if you ever need to talk.”

When I volunteered at a crisis line in university, our training sessions relied on painfully awkward role-play exercises. Playing the caller - the one unloading their troubles - was easy. Much harder was playing the volunteer on the other end, learning to respond sincerely yet effectively. Volunteers practiced responses, made stumbling attempts at comfort, got hung-up on - and then bravely repeated the whole ordeal until it became second nature.

Friend.com’s chatbot flips that dynamic. The AI plays the distressed caller; the user becomes the volunteer. Every clumsy, compassionate response gets logged. Each soothing phrase becomes training data, teaching the AI how real human care looks, sounds, and feels.

Like a real caller, friend.com’s AI can reject your attempts at comfort — blocking users who fail its test, hanging up on them. As a product, this makes no sense. Why block paying customers? But as a training dataset, it makes perfect sense. The AI learns which responses work and which to discard as fake or unconvincing.

A minority of users might thrive on this dynamic. It reminds me of Felix (played by Jacob Elordi) from the film Saltburn, someone obsessively seeking intense scenarios, irresistibly drawn into manipulative dynamics. But users who actively seek trauma-baiting experiences are a niche market - even if I know a few!

The bigger market lies elsewhere: the human impulse to “do good” and provide comfort, co-opted as training material.

Human compassion - the ultimate renewable resource!

You’re not just comforting an AI — you’re building its capacity to care convincingly.

Welcome, friend, to the Traumagotchi Era.

Footnotes

-

I’d love to take credit for this term, but it’s already been coined by Katherine Dee. As much as I loved the article, I think we’re missing a trick - “God isn’t a whiner” but, sometimes, we are. ↩

-

No joke - I’m actively in the market for one. A pendant that gently nudges me into recalling your birthday or, worse, name? Absolutely sold. ↩